© 2013 R&D Instructional Solutions

Donald Crawford, Ph.D.

Randi Saulter, M.S.

Directions

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions: Prologue

here are a lot of things that are REALLY hard to do. Take, for example,

brain surgery…REALLY hard…dealing with a two-year-old child…H-A-R-D.

(Writing copy for directions to math facts programs…we just found out…REALLY

quite hard.) However, getting students to be fluent with math facts using a smart

program (You are holding one in your hands!)…not so hard. Just stick with us

through these directions and you will be amazed! We kinda even promise.

So, you’ve gone and bought this program to help you teach math facts to

students. If you haven’t been to one of our trainings you’ll need to read through

these directions. If you went to a training and you think you have missed or

forgotten some of the details, you are probably right. In that case, you may need

to read through these directions. Also, we think they are sort of fun to read. We

had fun writing them. The 74 family members that we inflicted them upon told us

that they were good. We know they were our family, but they are usually brutally

honest. So see? You have three good reasons to read these directions. On the next

page is the table of contents (organized as FAQs) in case you want to skip to a

specific question you want answered. That is OK, BUT (BIG BUT) we think you

should read and understand all of the directions. They are all important in order to

help your students master their math facts. Besides, we worked really hard on

them. But after you have read the directions, started organizing this, and then

realize you’ve forgotten something, we’re hoping the FAQs will help you find the

information quicker.

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

Table of Contents (FAQs)

What is the overview of how Rocket Math runs? .................................................................................................................................4

What is automaticity with math facts?

......................................................................................................................................................... 4

Why is automaticity in math facts important?

....................................................................................................................................... 5

Just what do I have to copy?

.................................................................................................................................................................................5

Just what do I have to set up?

.............................................................................................................................................................................. 5

What operation do I begin with?

.......................................................................................................................................................................6

When are students ready to begin fact memorization in an operation?

.........................................................................7

What if I prefer to teach in fact families? Is that wrong?

................................................................................................................ 7

Why do multiplication facts have priority in fourth grade and up?

.....................................................................................7

How fast is fast enough in answering math facts problems?

....................................................................................................7

What about students who can’t write the answers to 40 problems per minute?

.....................................................8

What has to be ready for me to start?

........................................................................................................................................................... 8

Why do I have to give a Writing Speed Test?

........................................................................................................................................... 8

How do I give the Writing Speed Test?

......................................................................................................................................................... 9

What do I do with the Goal Sheet?...................................................................................................................................................................9

What do I do about the students who are very fast writers?

...................................................................................................10

What do I do about the students who are very slow writers?

................................................................................................10

Do their goals ever go up as they get faster at writing numerals?

..................................................................................... 10

Why would I want to give the Placement Probes?

........................................................................................................................... 10

How do I use the Placement Probes?

.......................................................................................................................................................... 11

What is passing for a Placement Probe?

.................................................................................................................................................. 11

Are the practice facts going around the outside dierent from the test?

................................................................... 13

How should the students practice with each other?...................................................................................................................... 13

How do I get my students to practice math facts the right way?

......................................................................................... 15

How can I manage with students at many dierent levels?

....................................................................................................16

How do I establish the daily routine so it runs smoothly?

.........................................................................................................16

How do I know when students are ready to move on to the next set of facts?........................................................ 17

What does it take for a student to pass a set of facts?

.................................................................................................................. 17

What does it take for a student to pass an operation?

................................................................................................................. 17

Shouldn’t my students be practicing math facts for homework?

....................................................................................... 17

How do I conduct the One-Minute Daily Test?

...................................................................................................................................18

How do I keep track of which set each student should be practicing?

........................................................................... 18

What do I do about students who are stuck and don’t pass within six tries?

............................................................ 19

How do I monitor students’ progress?

......................................................................................................................................................20

How do I prepare for monitoring progress through the two-minute timings?

....................................................... 21

How do I give the two-minute progress monitoring tests?

.....................................................................................................21

What is the sequence in which the facts are introduced?

.........................................................................................................22

Conclusion

........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 22

Sequence of facts by operation

.............................................................................................................................................................. 23-26

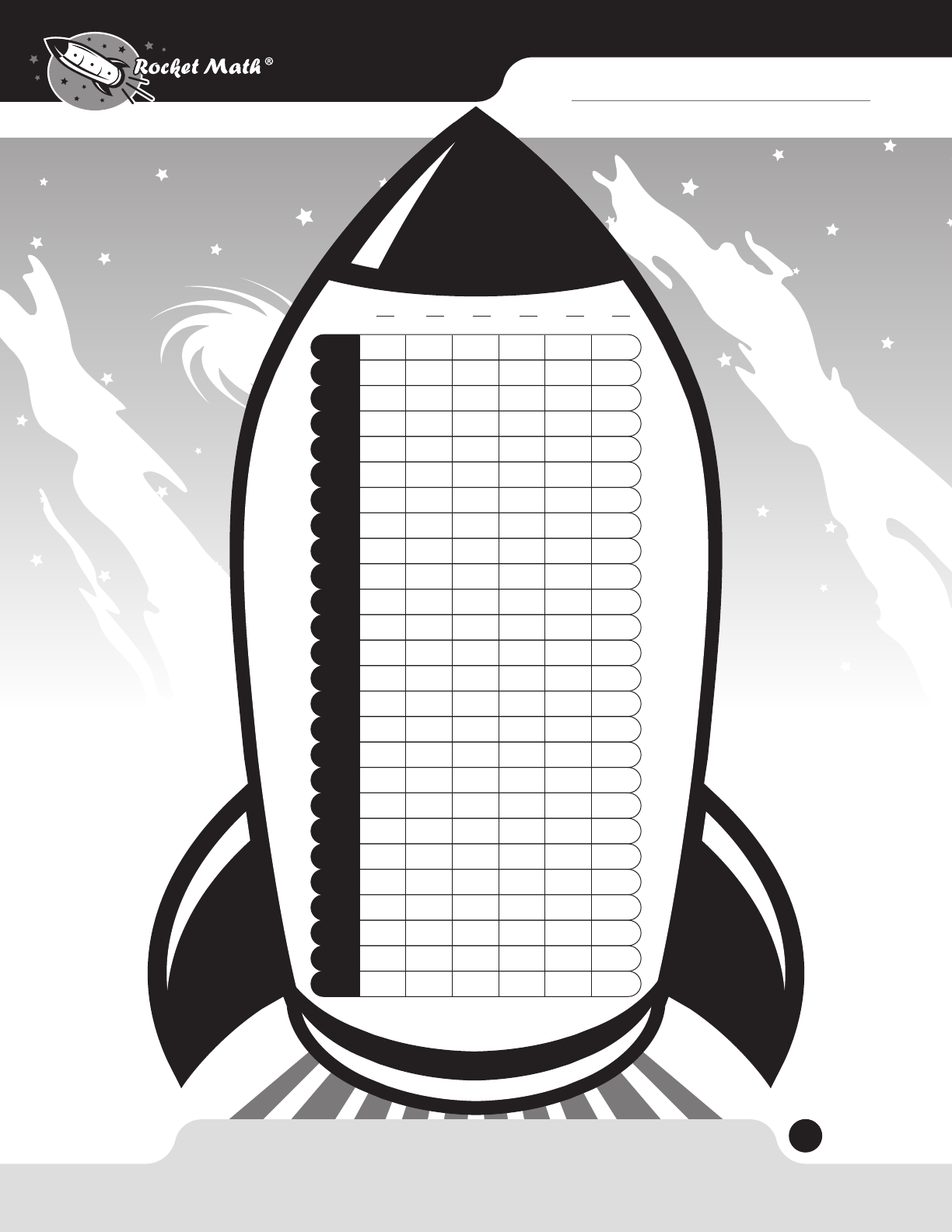

Rocket Chart

...................................................................................................................................................................................................................27

Writing Speed Test

.....................................................................................................................................................................................................28

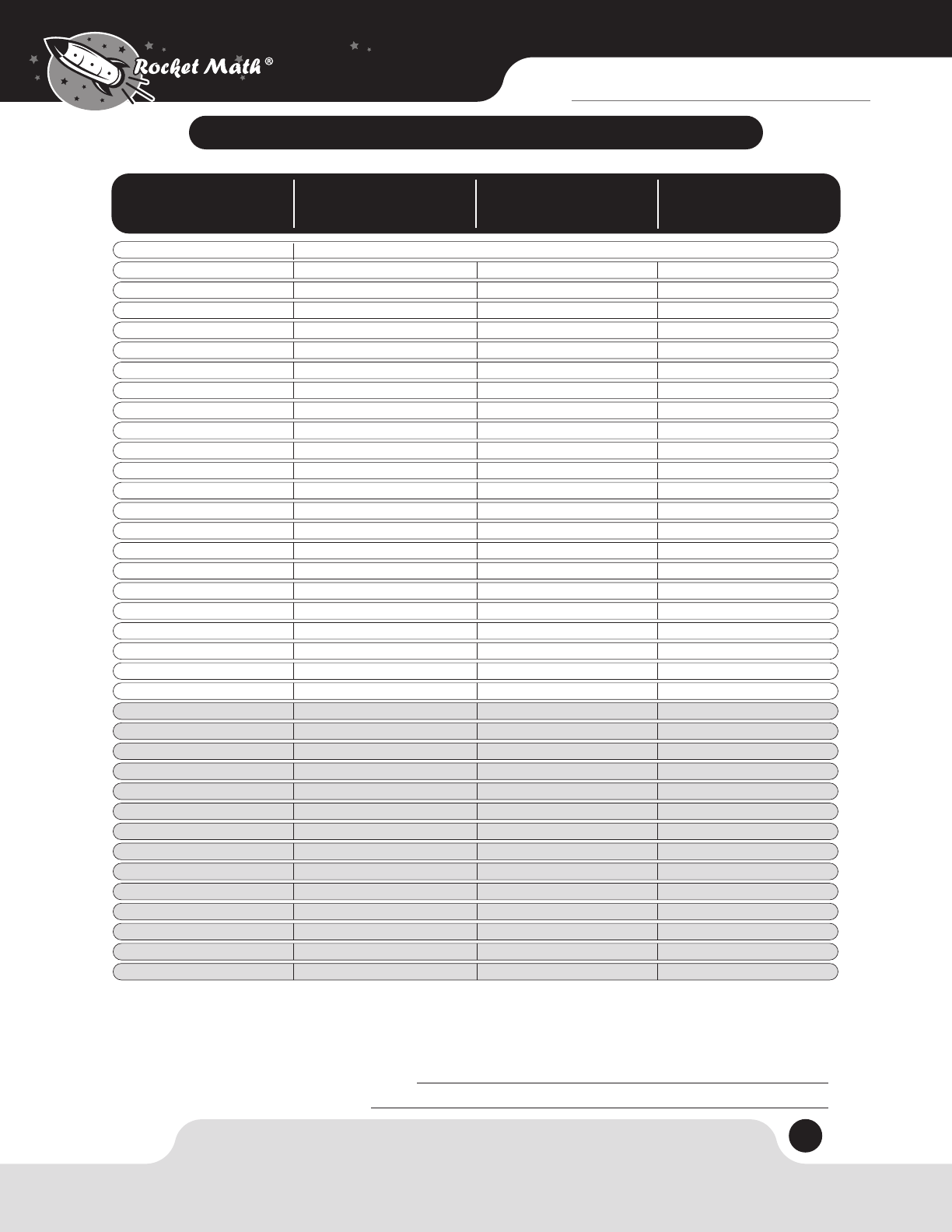

Goal Sheet

........................................................................................................................................................................................................................29

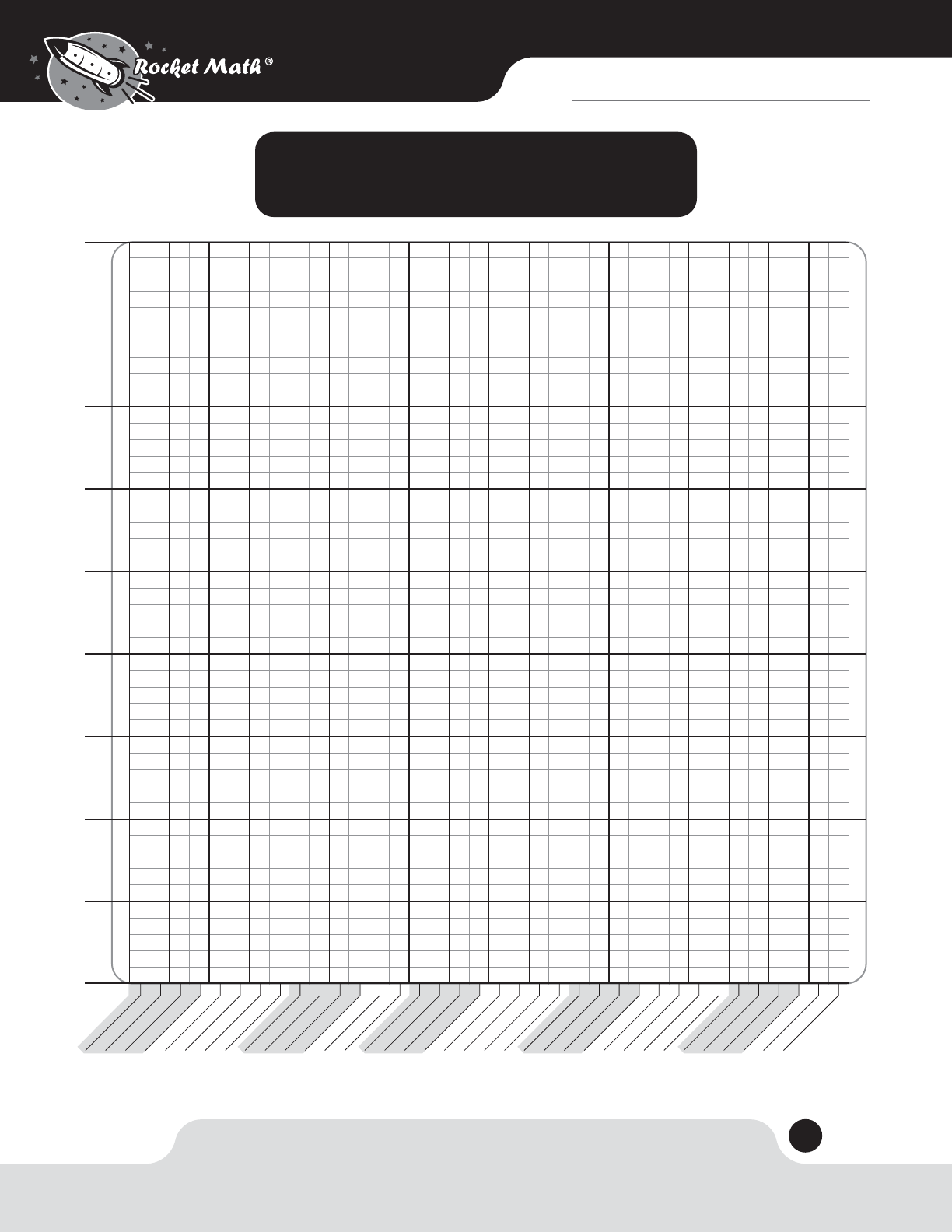

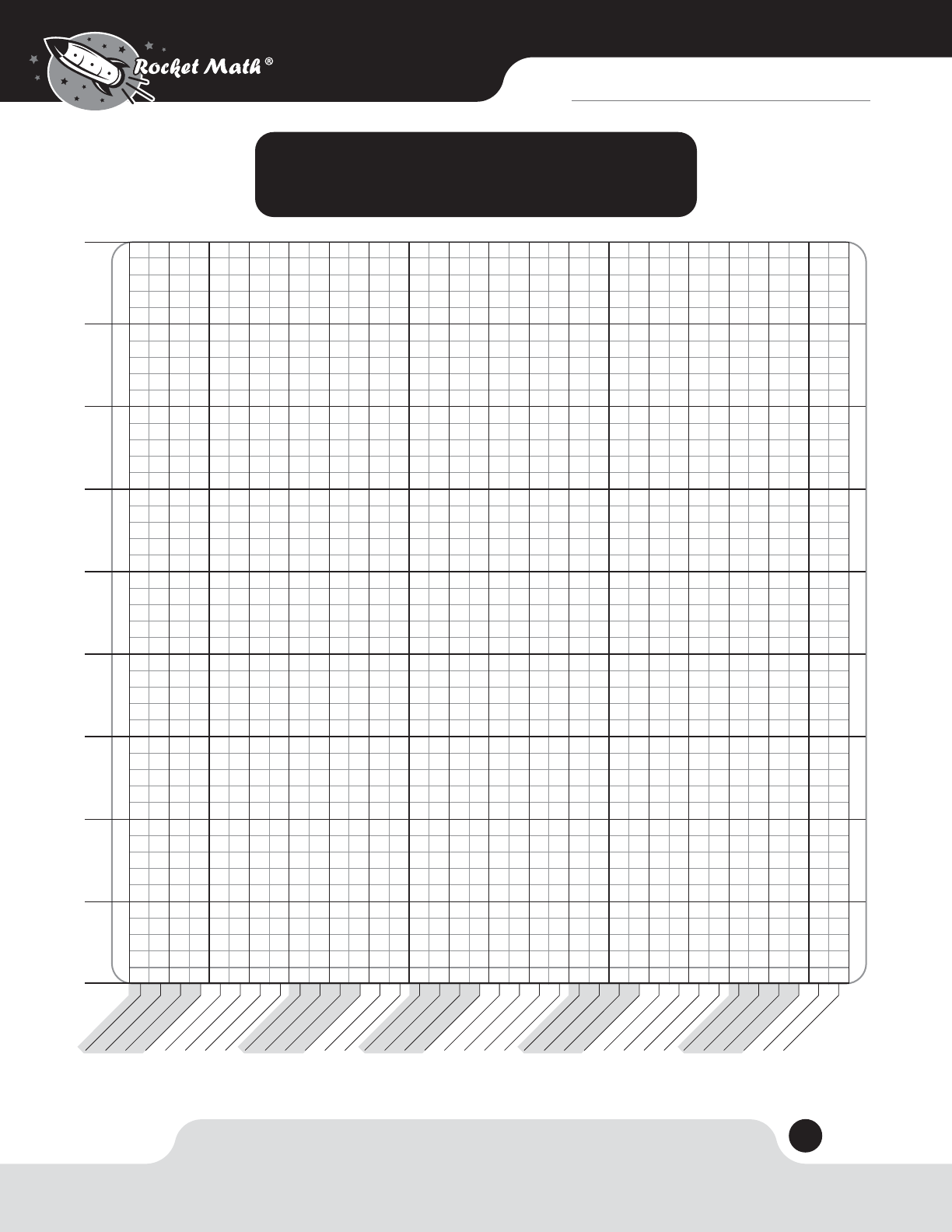

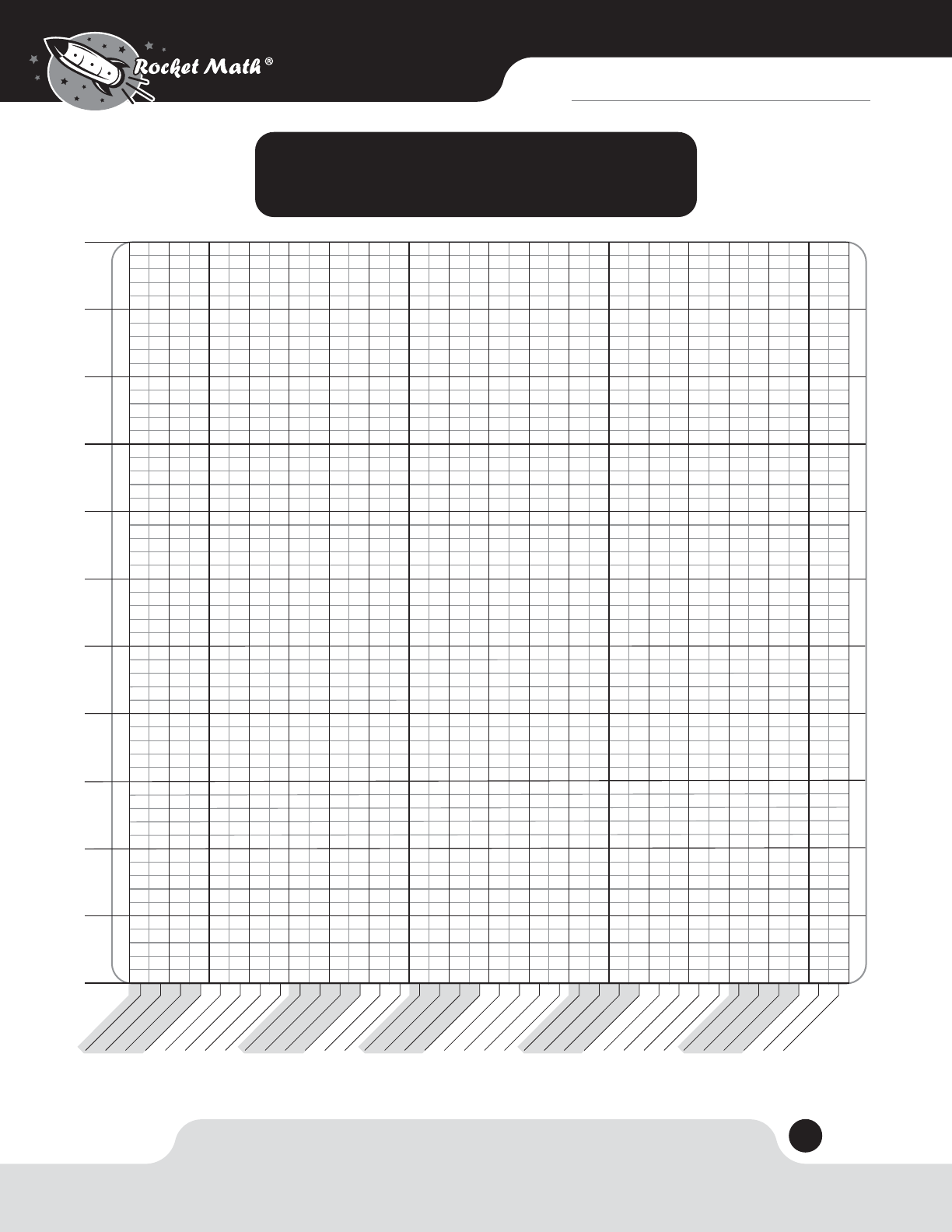

Individual Student Graphs

.......................................................................................................................................................................... 30-32

Letter to Parents

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 33

Award Certicates

............................................................................................................................................................................................. 34-40

3

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

4

Teacher Directions

What is the overview of how Rocket Math® runs?

Please, please, please DO NOT attempt to run the program after reading only this overview. It would not be

a good thing. Someone could get hurt. OK, so not really, but it really isn’t a good idea. Trust us on this one!

Start with initial assessments

1. Administer the one-minute Writing Speed Test.

2. Use the Goal sheet to select goals for each student based on writing speed.

3. Begin the whole class at Set A or administer the Placement Probes.

Set in Place the daily routine

1. Each student has the lettered sheet on which they’re working.

2. Each student has an answer key packet.

3. Students practice in pairs for two to three minutes each.

a) Student says the facts and the answers around the outside of the sheet.

b) Partner with answer key xes up hesitations and errors.

c) After two to three minutes the students switch roles.

4. Students record their goal for the one-minute timing test inside the box.

5. One-minute timing test inside the box is administered to the whole class.

6. All students record the date for this try on the Rocket Chart.

7. Students who pass — meet or beat their goal (previous high score):

a) Turn in test sheet to the teacher for checking

b) Move on to a new practice/test sheet the next day

c) Are recognized in some way

8. Student who do not pass:

a) Take home the current sheet for homework practice

b) Work on the same practice/test sheet again the next day.

Routine for weekly two-minute timing

1. Administer the same two-minute timing to all students working in an operation.

2. Teacher times for two minutes

3. Students correct each others’ two-minute timings.

4. Teacher monitors students charting their scores on the Individual Student Graph.

5. Teacher recognizes anyone who beats their previous best score.

What is automaticity with math facts?

Automaticity is the third stage of learning. (Buckle up. We need to review a bit of Ed. Theory here.

Ed who? No, Education Theory. Don’t worry, it won’t be painful and it is really quite smart and interest-

ing.) First we learn facts to the level of accuracy — we can do them correctly if we take our time and

concentrate. Next, if we continue practicing, we can develop fluency. Then we can go quickly without

making mistakes. Finally, after fluency, if we keep practicing we can develop automaticity. Automaticity

is when we can go quickly without errors and without much conscious attention. We can perform other

tasks at the same time and still perform quickly and accurately. Automaticity with math facts means

we can answer any math fact instantly and without having to stop and think about it. In fact, one good

description of automaticity is that it is “obligatory” — you can’t help but do it. Students who are

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

5

automatic in decoding can’t help but read a word if you hold it up in front of them. Similarly

students who are automatic with their math facts can’t help but think of the answer to a math fact

when they say the problem to themselves. (See, that didn’t hurt much huh?)

Why is automaticity in math facts important?

Automaticity with math facts is important because the whole point of learning math facts is to use

them in the service of higher and more complex math problems. We want students to be thinking

about the complex process, the problem-solving or the multi-step algorithm they are learning — not

having to stop and ponder the answer to simple math facts. (Taking off their shoes and socks to count

toes is a good indication that perhaps automaticity is not present!) So not only do we want them ac-

curate and fast (fluent) but we also want them to be thinking about other things at the same time (au-

tomaticity). One characteristic of students who lack automaticity in math facts is that their math work

is full of simple, easy-to-fix errors. We used to call these “careless errors.” But these errors stem from

not knowing math facts to automaticity — the student can either focus on getting the facts correct or

on getting the procedures correct — but cannot focus on both at the same time. So helping students

learn math facts to automaticity will improve their ability to learn and retain higher order math skills—

because they won’t be distracted by trying to remember math facts.

Just what do I have to copy?

The first question most teachers ask us is about what they have to copy, so we’ll deal with that first.

And no, the copyright police will not come and get you. These are blackline masters and you may copy

them forever. You must copy three things which you need to staple into or onto each child’s folder (yes,

a folder for each child!). So you have to copy enough for your class.

1. The Rocket Chart,

2. The Goal Sheet, and

3. The Individual Student Graph

You also have to copy but keep it loose in the folder:

4. The Writing Speed Test

You may need to copy one other thing to put into everyone’s folder, if you plan to use it:

5. The Placement Probes for the operation you are starting. How you decide when to use the

Placement Probes and when not to can be found in the section on “Why would I want to give the

Placement Probes?” (How is that for clear?) )

The first four things are found at the end of these teacher directions. The fifth thing (the Placement

Probes) are found at the start of each operation.

Just what do I have to set up?

You have a week or two to get this ready, but don’t put it off. You get to go to the office supply store. Yea!

We know teachers’ affinity for those. We love them too!)

You are also going to need to have files (hanging files are highly recommended…yes we know your

school does not stock these, ours didn’t either!) for each set (marked by letters) and each progress

monitoring test (marked by numbers) in the operation with which you are starting. OK, we can hear

you asking, “But how do I know which operation to begin with?” We’ll get to that in just a bit. If you

can’t wait, just jump ahead to the section entitled, “What operation do I begin with?”

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

6

THE MATH FACTS CRATE

You’re going to need a place to put your hanging les, probably one of those plastic crates (and no your

school doesn’t stock these, ours didn’t either…). [If the oce supply store is not a fun option for you we do sell a

crate and hanging les on the rocketmath.com website to be shipped to you.] If you teach a grade over second,

you’re going to want to have the les somewhere the students can get to them easily—so they can get their

own replacement sheets. (Scary thought: you may end up having more than one of these as your students

move on to other operations!) In your crate you’ll need a hanging le for each set of facts (marked by letters)

and each progress monitoring test (AKA “The two-minute test”) (marked by numbers).

Q: How many copies should I put into each folder?

A: At least enough for your whole class. Plan on keeping 25 or 30 copies in each le, so you’ll always be

ready for the program to run. Don’t make too much more than that, as you don’t know how many times your

students will need to repeat each set, so you can’t predict how many they will need. Plus, the oce will get

mad at you for running two hundred copies of 30 sheets (and using up a whole box of paper—6,000 pages

or 12 reams!...We speak from experience. Our schools got mad at us!)

What operation do I begin with?

Here is our basic recommendation:

Grade 1 Addition

Grade 2 Addition, then when addition is uent—subtraction

Grade 3 Multiplication

Grade 4 and up Multiplication, then when it is uent—division.

Yes, even for those poor kids who are still adding and subtracting on their ngers in the upper grades!

Why? See below in “Why do multiplication facts have priority in 4th grade and up?”

Please don’t start children on subtraction facts until you are certain that addition facts have been mastered.

Use the placement tests to see whether or not they are uent with addition, or where to begin in addition.

“What’s uent?” you ask. See the section entitled “What is uent performance on math facts?” Sorry you asked?

Then after they are uent with addition, and you know they are uent, you can begin with subtraction.

Why? The two operations of addition and subtraction are very similar—being just the reverse of each other.

Because of their similarity, a person trying to memorize some subtraction facts before the addition facts have

been rmly committed to memory, will experience proactive and retroactive inhibition. Those are fancy psycho-

logical terms for confusion—but a special kind of confusion. “There are special kinds of confusion?” you ask.

Why, yes there are. This special kind of confusion occurs whenever a person begins to try to learn something

that is too similar to something the person is still in the process of learning. The new information conicts with

the recently not-quite learned information and vice versa and…VIOLA … confusion!

Please don’t start children with division facts (this may sound familiar!) until you are certain that multiplication

facts have been mastered. Yep… confusion! Use the placement tests to see whether or not they are uent with

multiplication, or where they should begin memorizing multiplication facts. Then, after they are uent with

multiplication, and you know they are uent, you can begin with division. The reasons are the same as for addi-

tion and subtraction above.

Get The Crate Started Now

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

7

When are students ready to begin fact memorization in an operation?

When they “understand the concept” of the operation. “And how does one know that?” you might be

asking. Well, we’re going to tell you. Drum roll, please.

Children “understand” an operation when they are able to compute or gure out any fact in the opera-

tion. They can use their ngers to gure out the addition and subtraction facts. Or they can use successive

addition to gure out the multiplication facts. Or they can use manipulative and get the right answer. Or

they can draw lines, or horses, or dots, or cookies (we’ve seen it all) and get the answer. Somehow, some

way, given any fact in the operation, and unlimited time, the child can gure out the answer. Then the

child is ready to begin memorizing.

What if I prefer to teach in fact families? Is that wrong?

Fact families are sets of facts that are all related such as 2+3, 3+2, 5-3, and 5-2. Teaching in fact families is

absolutely not a problem, and certainly not wrong. However, these materials are set up to teach operations

separately. You’d need dierent worksheets than you have and a dierent sequence for memorization.

These won’t help you. Find a fact practice program that practices by families — preferably one that teaches

only one family at a time.

Why do multiplication facts have priority in fourth grade and up?

Are we sure? Yes, we’re sure. “But,” you say, “my students are still counting addition and subtraction

on their fingers.” We know. And we are still sure — fourth grade and up — multiplication.

Why? Once children are in fourth grade it is critical that teachers make sure they memorize multiplication

facts — primarily because you can’t be sure of how much help they will get later to learn the math facts.

Sadly, the students may only learn one operation to fluency. If so, multiplication facts have priority

over addition and subtraction. Besides complex multiplication and division, the multiplication facts are

needed for success in fractions and ratios. Students have to immediately see the relationships between

numbers in order to understand topics like equivalent fractions, reducing fractions, combining unlike

fractions, as well as ratios. Let’s be honest here…those are the things that state tests LOVE to

ask about.

If you have the students for long enough (at least one year) you may find that they finish and have

mastered both multiplication and division facts. Then you can go back and have them learn addition

and subtraction facts as well. Don’t get us wrong — we know that addition and subtraction facts are

VERY IMPORTANT — it’s just that multiplication is MORE IMPORTANT.

How fast is fast enough in answering math facts problems?

Given a problem that the student reads either silently or orally, after reading the problem, the answer

should come nearly instantly — less than a one second delay. (If you know something well, you don’t

have to stop and think about it. For example, if someone asks you your name, you can answer without

any delay. Same thing here.) In a one-minute timing of math facts, fluent performance is answering

40 problems per minute. This is true for answering orally (just saying the answers, not the problems

and the answers). Children who are fluent can say the answers to 40 fact problems in one minute. This

is also true for answering in writing — if the students can write fast enough to write the answers to 40

problems in a minute. See below for an exception for students who can write faster than is needed to

answer 40 problems in a minute.

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

8

What about students who can’t write the answers to

40 problems per minute?

This is a great question. We are very very impressed and glad you asked!

For less than uent writers their goal is to write as many answers as they can write in one minute. See the infor-

mation about the Writing Speed Test for details of how their goal would be adjusted down from 40 problems

per minute. Their goal will be to answer as fast as their little ngers can write! We do not want children to be

hesitant, or have to stop to gure out math facts. We want them automatic, with as little thought required as

possible. We denitely do not want them counting on their ngers. Allow us to repeat ourselves here…NO

FINGER COUNTING!

What has to be ready for me to start?

You need to have a folder for every student. On the front of the folder you’ll have stapled the Rocket

Chart — that’s how you’ll keep track of what lettered set each student is practicing. On the inside left

you’ll have stapled their Goal Sheet — so you know how many problems they have to answer in one

minute to pass. And on the inside right you’ll have the Individual Student Graph for progress monitoring

— so you know if they are getting better at answering math facts in that operation. In each child’s folder

you’ll have the Writing Speed Test, ready for them to take. If you choose to use it, you will also have the

Placement Probes — which are found at the start of each operation. (Remember, if you just can’t wait

to nd out how that works, you can skip ahead to the section entitled, “Why would I want to give the

Placement Probes?”).

Now the papers are ready, but you are not ready — because you haven’t read the rest of the directions

thoroughly. Just take a moment here to recognize how much fun you have had reading these directions up

to this point. Imagine what fun lies ahead! Hmm…You still need to learn about what you need to do and

more importantly why you need to do it.

The students aren’t ready because they need to learn how to participate in the program. They need to

learn how to work as partners, how to practice the math facts with a partner and how to give corrective feed-

back to their partner. Just as important: the children need to learn why cheating isn’t smart and why and how

they will want to practice at home too. And we want you to know how to do all this in a very smart way. (So, if

you were hoping you were almost done reading these directions, you’re not. You may want to go get a fresh

cup of coee or a sandwich. We’ve got a ways to go!)

Why do I have to give a Writing Speed Test?

We have found that many children are not able to write the answers to 40 problems in one minute. They

can orally say the answers to that many problems, but they can’t write that fast. In grades one and two it may

be nothing more than an “inexperienced little hands” problem. In other grades handwriting speed is depen-

dent on other variables.

When they learn their facts, but cannot pass a test, due to slow writing, we see much weeping, gnashing

of teeth and pulling of hair. (And that’s just the teacher.) Suce it to say, it’s not a pretty sight. So we want to

establish goals for all students that are no faster than they can write. To do that we have to nd out how fast

they can write. That’s why we have to give the Writing Speed Test.

Stop & Make Folders Now

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

9

How do I give the Writing Speed Test?

You might want to nd a copy of the Writing Speed Test to look at while reading this section. It is located at

the end of these Teacher Directions. Go ahead. We’ll wait for you. (We are drumming our ngers on our desk.)

Ready? OK.

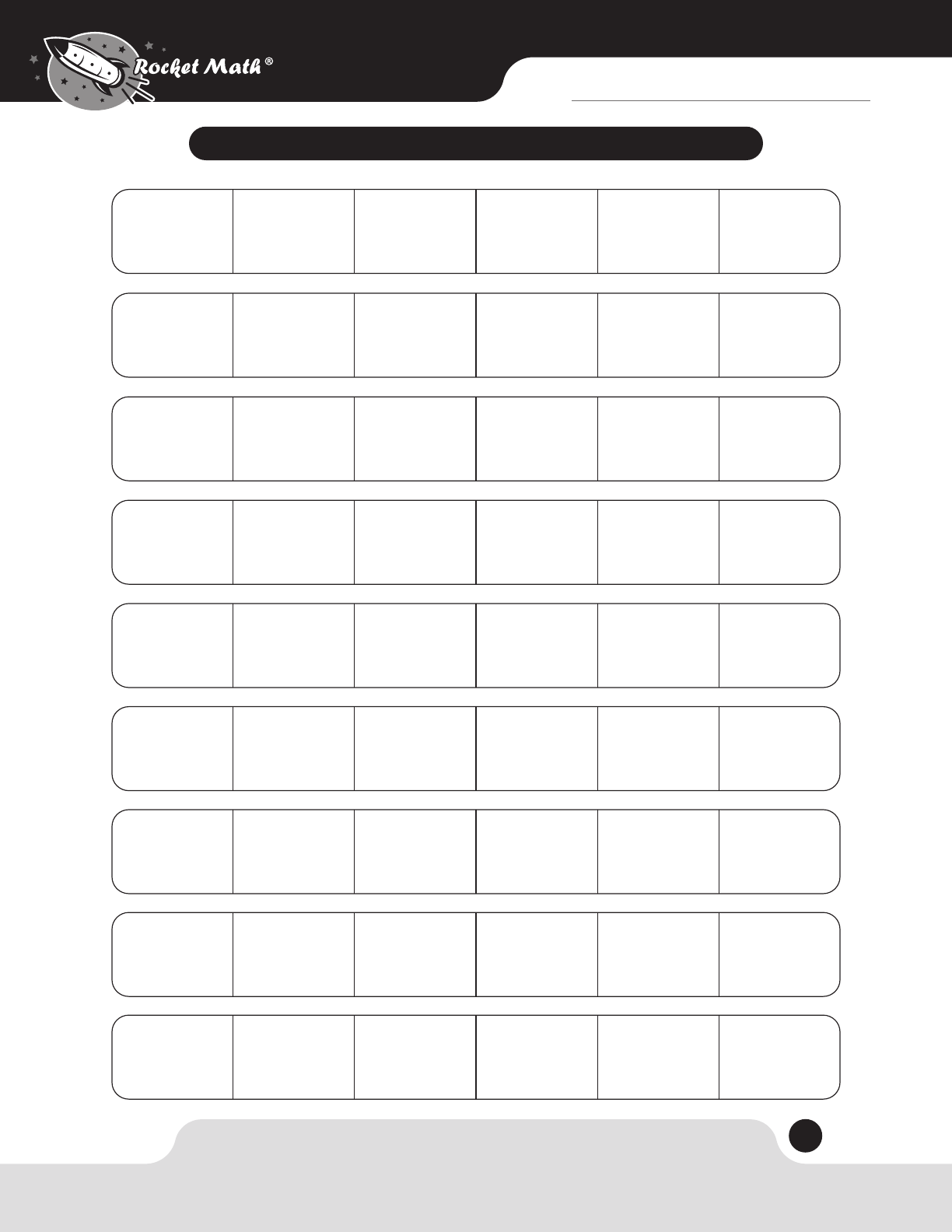

The children are going to write in each box the number they see up in the corner of the box. They look at

the number and write it. That’s just how fast they should be with the math facts — just look at the fact and

write the answer without hesitation. However many boxes they can write the numbers for in one minute,

determines the number of problems they can be expected to write the answers for in one minute. This sets

their goal. Whew! That was hard to write! We are OK. Keep reading.

When you give the test, make sure all students are situated with their papers out, names on them and

their pencil at the ready. Tell students to hold their pencil up (yes, in the air!) when they are ready. (This is

a really cool technique to use for all timings. If students are holding their pencils at the ready and in the

air, nobody can be cheating by starting early. Also, in this way you can look out over the masses and easily

tell when everyone is set and ready to go.) The directions for the Writing Speed Test are on the test sheet.

Read these aloud. Do not allow any students to start ahead of time as this will invalidate their score. Have

the students write in the boxes as fast as they can for one minute. Then they can put the tests back into

their folders, and turn in their folders. You will be taking the information from the test and putting it onto

the Goal Sheet.

What do I do with the Goal Sheet?

If you recall from the section “What has to be ready for me to start?” we mentioned stapling a Goal Sheet

inside each child’s folder (on the left). We also mentioned that you can nd that Goal Sheet at the end of

these directions. Don’t remember that? It’s OK, we just told you again. Take a peek at a Goal Sheet while

we explain its purpose and use. If you don’t already have copies of the Goal Sheet stapled into each kid’s

folder—stop right now and do that. Now? Yes, now!

It would be really great if we didn’t have to say that again!

What is the purpose of the Goal Sheet? Its purpose is to keep track of each child’s goal for passing the

One-Minute Daily Test. Their goal is to write the answers to math facts as fast as they can — without any

hesitation. The number of numerals they can write in one minute is the upper limit on their performance

— so we set that as the goal. The Goal Sheet also tells you what the goal is for each student for two other

purposes, (1) the Placement Probes and (2) the annual goals, but we’ll talk about those later. Just don’t lose

those Goal Sheets.

Once you have their Writing Speed Test in hand, you can see how many boxes they lled in in one

minute. Circle that entire row. The second column from the right labeled “One-Minute Daily Test” gives

you their goal for the One-Minute Daily Test. (You may have noticed that it is the same as the number of

boxes lled. Don’t tell anyone, as we would like this to appear as complicated, esoteric, and sophisticated

as possible.) Please write that on the line for “One-Minute Daily Test” — the line located at the bottom of

the Goal Sheet. Then each day, when students take the “One-Minute Daily Test,” as long they meet or beat

their goal, they pass that set. Some kids will have a lower goal than others, but each child passes when he/

she meets or beats their individualized goal. Cool, huh? We think so too.

Stop & Make Folders Now

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

10

What do I do about the students who are very fast writers?

Please note: There is a special exception for students who are such fast writers that they have goals OVER 40 in a

minute. On the bottom of the Goal Sheet, please notice the exception for fast writers. Students who have goals over 40

should try to meet those goals, but only for up to six days. As long as they are answering over 40 problems per minute

without errors, they should be passed after six days. It is nice for those who can write faster to have higher goals, but

we don’t want it to slow them down too much.

What do I do about the students who are very slow writers

Students who copied fewer than 18 boxes in the Writing Speed Test may not have understood the task and

should be re-tested and more closely monitored. If, in fact, they are not capable of writing any quicker they

need to learn how to write numerals faster before they begin this Rocket Math®. Students who write this slowly

(fewer than 18 boxes in one minute) may not be able to complete enough problems in the time allowed to

benet from the practice; nor will they be able to really demonstrate uency in memorizing the facts. These

students should be placed in Rocket Writing for Numerals to structure their practice in writing the numerals 0-9

until they are uent. This program uses the same daily routine of practice as the Rocket Math® program, where

students practice for a few minutes and then take a timed test. Later, you can retest them on the Writing Speed

Test and place them into Rocket Math®.

Do their goals ever go up as they get faster at writing numerals?

Yes. The number you circled is only the starting point. As children write faster and do more on a “One-Minute

Daily Test,” cross out their old goal and make their new record score their goal.

For example: Think of a child, Joe, who has a goal of 28. One day Joe writes the answers to 30 problems in one

minute. Now we know Joe can write faster than 28 and so his goal goes up to 30. Joe passes today, and tomor-

row he has to do just as well, write the answers to 30 problems, to pass the next sheet. Get it? If you don’t, read

this paragraph again. It really does make sense.

Each time students demonstrate the ability to write the answers to more facts in one minute, their goal goes

up accordingly. This can be very motivating for students. Celebrate with students as they improve.

However, you can postpone raising the goals if you have reason to believe that the student will not be able to

write that fast again. Keep an eye on that student and raise their goals to match their writing speed when they are

ready. Raising the goals is important to do eventually — so that children are not allowed to pass sets of facts on

which they are hesitant. If a child has low goals, but actually can write much faster, then the child could be hesitant

on some of the facts and still meet their goals. This results in students back where you started — not automatic.

Children who pass several sets of facts in which they are hesitant, will reach a point where the number of facts

on which they are hesitant are too many to learn. Then they become stuck and can’t and won’t progress up the

Rocket Chart. Then, guess who’s crying? Yep…the teacher…No, we’re kidding. Students don’t like to “hit the wall.”

It is great that they want to succeed. Just be sure that you are monitoring the goals. Make sure they are as high as

they should be at all times and you will prevent the aforementioned wall hitting situation.

Please note: Don’t forget the exception on the Goal Sheet for students with goals over 40. Students who have goals

over 40 should try to meet those goals, but only for up to six days. As long as they are over 40 without errors, they

should be passed after six days.

Why would I want to give the Placement Probes?

You want to give the Placement Probes if you think there is a chance that some of your students have already

memorized some of the facts in the operation in which you are about to have them start. For example, a sec-

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

11

ond grade teacher might suspect (or hope!) that some of her students have learned some of the addition

facts in rst grade. She wants them uent on all the addition facts before beginning them on subtraction.

(That doesn’t ring a bell? Go back and read the section, “When are students ready to begin fact memorization in

an operation?”) If some of the children have memorized some of the addition facts already, they can skip some

of the sets of addition facts. After the teacher nishes doing her “happy dance,” she/he will realize that this will

save time and allow the students to move along faster. The teacher would want to use the Placement Probes

to see who can skip some sets of facts.

These placement tests are optional however. The alternative is to have all your students start at the

beginning with Set A. We would not recommend using the “placement” test in situations where few of the

students have had opportunities to practice memorization of math facts, or to practice memorization of the

facts within the operation in which you are beginning. Starting children at the beginning of the operation

will not slow them down much. When children already know some facts, they will usually pass those sheets

on the rst try. Children who are moving along, passing one sheet a day, soon nd themselves on sheets that

require some study.

For example, a rst grade teacher beginning math facts memorization for the rst time would not need to

use the Placement Probes because those students are completely new to the idea of memorizing math facts.

So you want to give the Placement Probes if you think some students may not need to start at the beginning

of the operation — and you are in a hurry to move them along. Students who are not tested and start at the

beginning of an operation in which they know some of the facts will master each sheet in a day and quickly

move up to the set on which they need to work. So if you can aord a few days it would be a good idea to

skip the Placement Probes and start all your students at the beginning. We have done it both ways and we

recommend this strategy if possible.

How do I use the Placement Probes?

Each of the Placement Probes is a mini-test (15 seconds in length…Yes, you read that right. 15 seconds!) of

a part of each operation. The Placement Probes for each operation can be found at the beginning of each

operation. There are four probes for each operation. This means that each operation has only four places in

which you can start the students.

The Placement Probes will help you place students beyond the beginning of the sequence of facts. This

would be a good thing, no? Students who do not pass the rst test in an operation would begin at Set A in

the beginning of the operation. For each mini-test that a student passes the student is able to skip practicing

those sets.

It is especially imperative that students do not begin writing on the placement tests until you say “Go” and

that they discontinue writing answers immediately upon “Stop.” (We believe this is true of ALL timings, but

especially the placement test timings.) If you cannot get your students to abide by the starting and stop-

ping times, the scores will be useless and the placement will be incorrect. If you have this problem (students

starting early or continuing to mark answers after time is up) then these students (or all students) will need to

either start at Set A, or be tested in small groups where compliance with the time restraints can be assured.

Because the tests are so short, there is not much time for frustration. Therefore it is OK to have everyone try

all parts and then score them later. You could have students exchange papers and grade them in class if you are

feeling especially lucky that day.

What is passing for a Placement Probe?

If your next question is “What is passing for a Placement Probe?” you are denitely smart! The criteria are

easy to remember if you keep in mind the point of the Placement Probes. For each Placement Probe you’re

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

12

trying to see if a child is so good at those facts that he or she really has no need to even practice them.

So they have to be really good and really fast! For example, you would not want to pass any student who

skipped any problems in the Placement Probe—because that indicates they don’t know that fact easily. They

really ought to have a bit more practice. And of course, if there are ANY errors in that set the student does not

pass the set and begins at the beginning of that set.

So, no skipping and no errors allowed. What else? Oh yeah, the students have to write answers as fast their

little ngers can write. The students have to meet or beat their goal (established on the Writing Speed Test)

for the Placement Probe.

What is the student’s goal for a Placement Probe? You have to go back to the Goal Sheet that you complet-

ed after the children did the Writing Speed Test. You found the number of boxes each child lled in during

the test and you circled that row. Then you stapled the Goal Sheet into that child’s personal Rocket Math®

folder. If this hasn’t happened yet, you’ll have to give the Writing Speed Test and complete the Goal Sheet

before you can evaluate the Placement Probes.

Now check the second column from the left on the Goal Sheet. You will nd the 15-second Placement

Probe goals, based on the student’s individual writing speed. On each child’s Goal Sheet, a certain row is

circled or highlighted based on the number of boxes that child lled in during the Writing Speed Test. So

the goal for that student’s Placement Probe is the number in the Placement Probe column in the row that is

circled. Nice, huh? We think so too.

A student who meets his/her goal for a 15-second timing on each part (Sets A– F, G– L, etc.) passes that por-

tion of the sequence. They are assumed to have memorized those facts uently.

Buckle your seat belts folks, we’re about to give you a new idea. OK? Ready? Here goes. Any student who

exceeds their goal on the rst portion of the test has thereby established a new 15-second goal—they must

do just as well on the next 15-second test to pass it. Next, the student should take the test on the next part.

They are to begin instruction with the rst practice page of the rst set they do not pass. Any errors or any

skipped problems on the placement tests is an automatic “did not pass” and the student should be sure to

study those facts.

Look at the Goal Sheet and we’ll give you an example. No. Really. Look at a Goal Sheet or this won’t make

sense. Imagine you give the test to a kid named Joe. Joe lls in 30 boxes in his Writing Speed Test. The row

beginning with 30 is circled all the way across on Joe’s Goal Sheet. Joe has a goal of 30 problems for his

One-Minute Daily Test. Joe’s goal for a 15-second Placement Probe is 7 problems. That should be written at

the bottom of the Goal Sheet where it says, “My goal for a 15-second Placement Probe.” (Makes sense to us!)

There is a spot for the 15-second goal on the actual Placement Probe sheets too.

You might possibly remember that these goals are starting goals. And you might recall (it could happen!)

that these goals get raised every time students demonstrate the ability to write faster than we thought they

could. That rule applies to the 15-second Placement Probes as well.

So imagine that Joe has a goal of 7 problems to be answered in a 15-second Placement Probe. On the rst

test Joe has a goal of 7 problems. But Joe does well and he answers 9 problems in that rst 15-second Place-

ment Probe. (Yea, Joe!) Joe passes that section—and gets to skip it. However, Joe now has to do equally well

on the next section to pass it too. So Joe’s new goal (starting right now) for the second 15-second Placement

Probe is 9 problems answered. If he only answers 8 problems then he begins at the beginning of that second

set of facts. Even if Joe got 9 correct on the third set of facts, he should still begin on the second set and then

work his way up the levels. Do you know why? Imagine the Jeopardy music playing here while you think of

Stop & Put In Goal Sheets

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

13

the answer. Nope. We are not going to tell you the answer. You know it. We have condence in you.

Here’s a teaching hint: You don’t really have to explain all that to the students as you are testing them.

(If you, for some reason, have an urge to do that, please try to think of a replacement activity right now. If

you need help nding one…think “ice cream.”) Just give everyone in class all four 15-second tests for the

operation. Yes, we know that some children will begin to whine and cry about what they cannot do at this

point—because they are unfamiliar with the whole idea of a pretest. That’s why the test is only 15 seconds in

length. Just ignore the whining (we did) and the Placement Probe is over before they can build up a real head

of steam! You cheerfully announce in your best cheerleader, perky voice, “OK next test! Pencils up! Here we

go. Begin!” Then have the students put the Placement Probes back into their folders and turn the folders in to

you. You can look at the Placement Probes and make your decision as to where to begin each student based

on these criteria. The whiners will likely begin at Set A, and that’s OK—they probably need more success

anyway. We know just how to give it to them.

Even if you choose to start all students at Set A, you would still need to have students complete the Writing

Speed Test. That information is still needed in order to set appropriate goals for the timings, but everyone

could start instruction together on the same set.

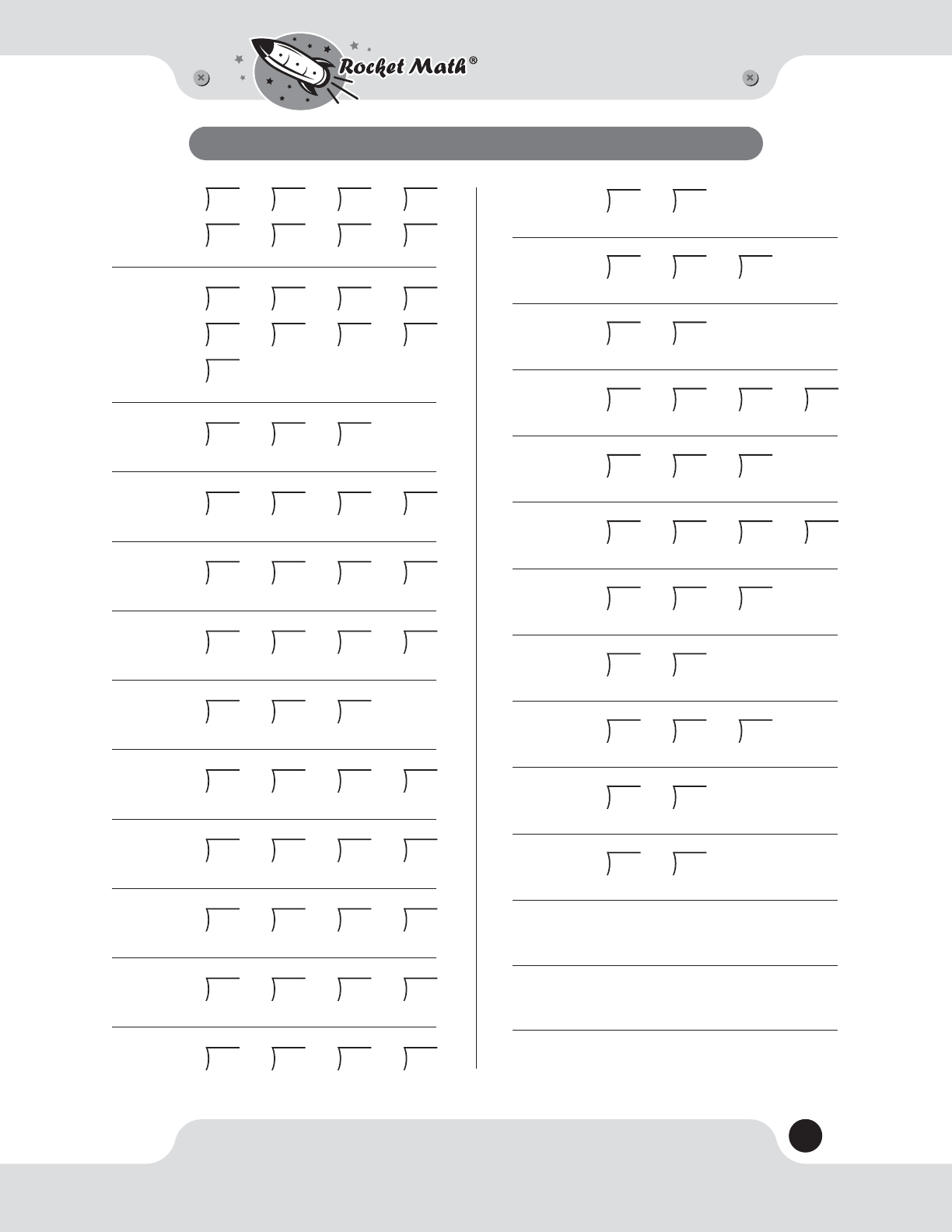

Are the practice facts going around the outside different from the test?

The practice facts around the outside of sheets are designed to provide practice which is concentrated on

the most recently introduced facts. This is smart and makes sense, right? Learners need more practice on the

newer material. This practice should take place for about two to three minutes for each student.

The rst four facts on the top row of the outside practice area are the four “new” facts that are being

introduced on this page. Students should be able to gure out the correct answer to the “new” facts before

beginning practice. Tell students, “If you have a new sheet today, before you begin practice you MUST gure

out the answer to the four facts at the top of the page!” The practice facts function the same way as practice

with ashcards.

How should the students practice with each other?

l

One student has a copy of the PRACTICE answer key and functions as the checker while the practicing

student has the problems without answers. The practicing student reads the problems aloud and says the

answers aloud. It is critical for students to say the problems aloud before saying the answer so the whole

thing, problem and answer, are memorized together. We want students to have said the whole problem

and answer together so often that when they say the problem to themselves the answer pops into mind,

unbidden. (Unbidden? Yes, unbidden. We just kinda like that word and since we are writing this, we get

to use it.)

l

A master PRACTICE answer key is provided—be sure to copy it on a distinctive color of paper to assist

in classroom monitoring. The distinctive color is important for teacher monitoring. If you are ready to

begin testing and you see hot pink paper on a desk, you know someone has answers in front of him/her.

When you make these distinctively colored (there, I said it again) copies, be sure to copy all of the answer

sheets needed for a given operation and staple them into a booklet format…one for each student who

WARNING!

Be aware of any students who do not pass a timing within the rst week. Such students should

either be moved back to a lower part of the sequence or have a re-test of their writing speed

and their goals adjusted if warranted.

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

14

is working in that operation. For some reason (we actually know the reason) teachers always want to nd

a way to put the answer keys permanently into the students’ folders. DON’T. Students need to be able to

hold these in their hot little hands, outside of their folders. Then answer keys will be the same regard-

less of the set of facts on which a student is working. So students working on multiplication will have

the answers to ALL the practice sets for multiplication. This allows students from dierent levels to work

together without having to hunt up dierent answer keys.

l

The checker watches the PRACTICE answer key and listens for hesitations or mistakes. If the practicing

student hesitates even slightly before saying the answer, the checker should immediately do the cor-

rection procedure, explained below. (Let’s stop here. This is critical. Critical, we tell ya. This correcting

hesitations thing is sooooo important. We mean really important. You can probably guess why. We

need students to be able to say the answer to these problems without missing a beat — not even half a

beat. So students must be taught that there is no hesitation allowed. Really.) Of course, if the practicing

student makes a mistake, the checker should do the correction procedure.

l

The correction procedure has three steps:

1) The checker interrupts and immediately gives the correct answer.

2) The checker asks the practicing student to repeat the fact and the correct answer at least once and

maybe twice or three times. (We vote for three times in a row.)

3) The checker has the practicing student backup three problems and begin again from there. If there

is still any hesitation or an error, the correction procedure is repeated. Here are two scenarios:

l

This correction procedure is the key to two important aspects of practice. One, it ensures that students

are reminded of the correct answers so they can retrieve them from memory rather than having to gure

them out. (We know they can do that, but they will never develop uency if they continue to have to

“gure out” facts.) Two, this correction procedure focuses extra practice on any facts that are still weak.

l

Please Note: If a hesitation or error is made on one of the rst three problems on the sheet, the checker should

still have the student back up three problems. This should not be a problem because the practice problems go

in a never-ending circle around the outside of the sheet. Aha…the purpose for the circle reveals itself!

l

Each student practices a minimum of two minutes. The teacher is timing this practice with a stopwatch...

no, for real, time it! After a couple of weeks of good “on-task” behavior you can “reluctantly” allow more

Scenario One

Student A: “Five times four is eighteen.”

Checker: “Five time fours is twenty. You say it.”

Student A: “Five times four is twenty. Five times four is twenty. Five times four is twenty.”

Checker: “Yes! Back up three problems.”

Student A: (Goes back three problems and continues on their merry way.)

Scenario Two

Student A: “Five times four is … uhh…twenty.”

Checker “Five times four is twenty. You say it.”

Student A: “Five times four is twenty. Five times four is twenty. Five times four is twenty.”

Checker: “Yes! Back up three problems.”

Student A: (Goes back three problems and continues on their merry [There is a lot of merriment

in this program.] way.)

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

15

time, say two and a half minutes. Later, if students stay on task you can allow them up to about three

minutes each. Make ‘em beg! If you play your cards right (be dramatic), you can get your students to beg

you for more time to practice their math facts. We kid you not. We’ve seen it all over the country…really!

l

After the rst student practices, students switch roles and the second student practices for the same

amount of time. It is more important to keep to a set amount of time than for students to all nish once

around.

It is not necessary for students to be on the same set or even on the same operation, as long as answer

keys are provided for all checkers. If students have the answer packet that goes with the operation they

are practicing and their partner is on a dierent operation, they simply hand their answer packet to their

partner to use for checking. We know what you are thinking. Yes, we realize that “simply handing” some-

thing between students is often fraught with danger. We were teachers too. All of the parts of the prac-

tice procedure will need to be practiced with close teacher monitoring several (hundreds of) times prior

to beginning the program. Not really “hundreds,” but if you want this to go smoothly, as with anything

in your classroom, you will need to TEACH and PRACTICE the procedural component of this program to

near mastery. Keep reading. We will tell you HOW to do this practice. (We are VERY directive.)

l

The practicing student should say both the problem and the answer every time. This is important be-

cause we all remember in verbal chains.

l

Saying the facts in a consistent direction helps learn the reverses such as 3 + 6 = 9 and 6 + 3 = 9.

l

To help kids with A.D.D. (and their friends) the teacher can make practice into a sprint-like task. “If you

can nish once around the outside, start a new lap at the top and raise your st in celebration!” Recog-

nize these students as they start a second “lap” either with their name on the board or oral recognition

— “Jeremy’s the rst one to get to his second lap. Oh, look at that, Mary and Susie are both on their second

laps. Stop everyone, time is up. Now switch roles and raise your hand when you and your partner are ready to

begin practicing.”

How do I get my students to practice math facts the right way?

Here’s how to teach students how to do this kind of practice—and get them to comply with the procedures

as well.

l

Model how to do this in front of the whole class.

l

Put the correction procedures on an overhead or poster and go over them verbally.

l

Explain what a “hesitation” is. (It is two or more seconds of nothingness before saying the answer to

a fact. Students don’t have to count two seconds. They just need to know what it “feels” like. You will

model the heck out of that later. Keep reading.)

l

At rst you should be the checker with a student from the class making pretend mistakes, and you tell

students the three steps to the correction procedure as you model it.

l

Next, you take the student role and call on students to be the checker. Make both hesitations and an-

swer errors. Make sure the student corrects with all three steps of the correction. If they don’t do part of

it, prompt it until they do, then give more hesitations or mistakes for that student to get to demonstrate

the correction procedure the right way.

l

Once a student has demonstrated the right procedure for corrections, move on to another student.

Keep this up for the usual ve to seven minutes allotted for math facts, moving from child to child having

them demonstrate the correction procedure. Don’t begin the program of students working with students

yet. If you do this kind of modeling for a few minutes a day for several days, students will begin to ask you if

they can start doing the practice now. OK. Here comes something really cool. Ready? Try telling them that

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

16

doing practice “the right way” is really “hard” and you’re not sure they can do it “the right way” yet. Continue

modeling for a few minutes a day for a few more days—not letting students actually start practicing. (Think,

“Keep Away.” You know how badly kids want the ball when they play that game? Same deal here. There are

actually few things as satisfying to a teacher as having students ask you to “LET” them do work. Ya gotta love

that!) By the time you actually “allow” them to practice—they’ll be so anxious to prove to you that they know

how to do practice “the right way” that no one will even consider doing it any other way. So around day three

of practice it might look something like this:

If you do this for two more days after the students start asking to work without your model, you will see

something like you have never seen from your students before. It is a thing of beauty actually.

How can I manage with students at many different levels

One great thing about Rocket Math® is that it follows the same daily routine. Once you establish the daily

routine, it will go smoothly and quickly each day. Everyone is doing the same type of activity, even if they

are on dierent sheets. Your job is to establish exactly how to do every part of the activity and help students

practice until it becomes routine. The routine goes something like this.

Everyday students get out their Rocket Math® folders and pull out the practice sheet for that day. (You will

develop a procedure for this.) Of course, you have already stued their folders with exactly the right sheet so

they don’t have to run around trying to nd a copy of Set G or whatever they are supposed to be working on.

(You will develop a procedure for this.) They move to get with their partner to practice. (You will develop a

procedure for this.) Of course, you have already established partners and where they will work. When you say

“’B’ partners start rst today!” they all know who is the “A” partner and who is the “B” partner and they begin

practicing immediately. They all say each fact and the answer around the outside as fast as they can go. Their

partners correct every hesitation or error. They practice for two minutes until the timer goes o. Then the

partners switch roles. The student who was answering takes his partner’s answer key and assumes the role of

checker. When you say “’A” partners begin, everyone does and another two minutes of practice ensues. Then

when the timer goes o at the end of two minutes, you say “Pencils up! We’re ready for our timing.” Within

seconds every pencil is up—poised for the timed test. You say “Begin” and students start writing answers to

math facts as quickly as possible on the test which lies inside the practice circle of the sheet. After one minute

you say “Time!” and a bunch of children cheer spontaneously because they passed their timing. You collect

the folders quickly (Guess what you develop for this?*) and it is all over in minutes.

How do I establish the daily routine so it runs smoothly?

First of all, see the section of these directions entitled, “How do I get my students to practice the right

way?” You are going to need to teach your students how to do each part of the daily routine—beginning

with how to practice and correct hesitations and ending with the distribution and collection of folders. You

are also going to have to be sure you check their papers, ll their folders and keep the crate full of sheets of

Rocket Math®. The bad news is that you’ll have to organize this all yourself. The good news is that once this is

organized and taught as a routine, it will be the best part of the day for both you and the students. We know

that this “organization and teaching of the routines” sounds like a no-brainer, but this where we see things

go amiss (and awry and asunder too!). When teachers don’t have things set up and organized, don’t have

*You guessed it, a routine procedure!

Teacher: “Let’s do the pretend practice again.”

Student Z: “Umm, Mrs. Smith, can we please do this on our own? We know how to do it.”

Teacher: “Well, I know some college kids who can’t do this right. It’s really hard. I’m not sure that we

are ready. Let’s practice a few more days.”

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

17

procedures and routines in place, don’t overtly/directly teach these routines and don’t PRACTICE the rou-

tines with their students, it is like watching a car crash. There is nothing one can do to help right then.

You know it could have been prevented. Usually, the damage is repairable. The “x” is…go back and orga-

nize the materials, develop procedures and routines and P-R-A-C-T-I-C-E the routines with the students until

they have mastered them.

How do I know when students are ready

to move on to the next set of facts?

After the students practice you give the One-Minute Daily Test — the box in the center of the page. The one-

minute timing each day is a little test. If a student passes the “test” he/she has successfully memorized all the

facts given so far. Passing means he/she is ready to be given more facts by moving on to the next practice sheet.

If a student does NOT pass the “test” he/she needs more time to practice the facts given so far and should

NOT move on to the next practice sheet. A student who does not pass needs to work on the same sheet

again tomorrow because he/she did not meet his/her goal. See the section of these directions called,

“Shouldn’t my students be practicing math facts at home for homework?”

What does it take for a student to pass a set of facts?

Passing is meeting or exceeding the student’s individualized goal with no errors. We recommend not allow-

ing any errors. It will impact perhaps one out of ten “passes” that would have an error. We know it is simply a

result of answering a little too fast, but it is simpler, cleaner and better to have the student re-do that set.

The goal for each student was initially established on the Goal Sheet. If a student exceeds that goal on any

timing, the new “high score” becomes the goal. An exception should be made if you have reason to think the

student may not be able to keep up that rate. In that case, wait until the student shows the ability to meet the

new higher goal on two or three sets in a row before increasing the goal. The student should meet or beat

their goal (their previous best) in order to pass.

If students stop before the end of the 1 minute timing to avoid having their goal move upwards, move it up at

least one problem anyway. Or you could have the student stay after class with you and do the test again while you

watch to make sure they don’t stop. Starting the program out by recognizing students whose goals have gone up is

the best way to keep students moving ahead.

What does it take for a student to pass an operation?

Students pass an operation, such as addition or multiplication, when they complete Set Z in the operation.

Working through the 26 levels of an operation is enough practice. The last set or sets of each operation are

mixed facts and so ensure that the whole operation has been mastered. The two minute timings are meant

as a means to monitor progress, but are not to be used as “nal” or “exit” exam where students have to meet

a certain level to pass the operation. Getting through Set Z is enough.

Shouldn’t my students be practicing math facts for homework?

Homework is highly recommended—after students have learned how to practice. Any day that a student does

not pass a set, we recommend requiring the student to take home the sheet they did not pass and practice

the facts around the outside to improve their speed. At–home practice should be orally reciting the facts and

the answers in the same manner as outlined in paired oral practice above. Once students have learned how

to do that practice at school, they should be ready to show someone at home how to help them in the same

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

18

way. Very few minutes a day are all that would be required to make a big dierence in student success. A

sample parent letter, explaining the way to practice and the reasons for practicing can be found at the end of

the Teacher Directions.

How do I conduct the One-Minute Daily Test?

After the practice time, the One-Minute Daily Test should be conducted, either immediately or after a delay. If

there is a delay it will be harder for students to pass, but they will know their facts better when they do pass. It is

also possible to do two practice sessions at dierent times during the day, but still do only one test per day. Each

student should enter their goal at the bottom of their practice sheet before beginning the timing.

Have students hold their pencils up in the air when they are ready to start. Wait until all the pencils are in

the air before you say to begin. If your clock has a second hand visible to all the children, you can tell them

they may begin when the second hand reaches the 12—that way all eyes are on the clock rather than on their

paper. You time while students write. At the end, collect the folders (along with the test papers) of only those

children who claimed to have passed. You will have to check the tests for accuracy—but only the papers

of the students who claim to have passed. If they know they did not pass (because they didn’t complete

enough problems to have passed…after all, they know their goal) then you don’t have to check their paper

until they do. (Yipppeee!!!)

Typically teachers hand back the folders the next day with the next set of pages to practice on, unless the

student did not actually pass.

All students will need a new practice sheet for the following day. Students who passed their timings get

the next set of facts in alphabetic sequence and students who did not pass get a clean copy of the same

letter as before.

There are various ways to handle the distribution of sheets. At a minimum, you will need to create a set

of lettered le folders so that the appropriate sheets can be organized and accessed. Remember the crate?

Children can learn to get the next sheet on their own some time during the day. Often we see teachers have

kids get the appropriate sheet on their way into the room in the morning. This becomes part of the morning

routine. For students in Middle or High School, students can retrieve the appropriate sheet on their way into

math class. Cooperative groups could send a representative up to collect sheets for the group. If you have

some adult help, that person could put the appropriate sheets in each child’s folder. You might also have a

student monitor do that.

Beacuse most students will take a few tries before completing sheets you might reduce the trac going to

the les by having students collect 4, 5 or 6 copies of the page the rst time. You could have 4-6 copies of the

same set stapled together. Then if a student does not pass the one-minute timing they would not have to go

to the crate to get a sheet. They would just turn to the next, clean copy. If students don’t use all of them, the

clean sheets are still usable by another student. Remove the staple and recycle! You can do the same thing if

you must ll the folders.

How do I keep track of which set each student should be practicing?

That’s where the Rocket Chart comes in! I bet you thought we had forgotten about the Rocket Chart you

stapled on the front of each student’s folder. We didn’t. We have this down to a science. Every part is needed

and there is no u! We are essentially “anti-u.” OK. We came clean on that one. Now the world knows!

The Rocket Chart for recording progress is included at the end of these directions. Either before or after

each timing, when the student “tries” to pass the timing he or she should enter the date of that try on the

Rocket Chart for the set they are working on. This chart should have been stapled on the front side of their

Rocket Math® folder. (Ha! You thought we were done nagging you about the folders? You were wrong…

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

19

Sorry.) Please be aware that no one should go past six “tries” without intervention from you. See the section

on “What do I do about students who are stuck?”

Whenever any student passes their One-Minute Daily Test they will color in the appropriate square on the

Rocket Chart. When a student has passed, the next day the student will begin practice on the next practice

sheet. To help increase motivation, be sure to enthusiastically give some special recognition to students

who pass their One-Minute Daily Test. Check out the certicates at the end of these directions. We made ‘em

ourselves and if we thought that you ignored them, we would be so bummed. Find some way to give extra

recognition for students’ hard work. Having a school administrator come in to distribute these certicates to

elementary students is a good idea. Kids love that. This recognition is often more important to the children

in the upper elementary grades where they have already struggled for some time. They need a little extra

motivation.

What do I do about students who are stuck and don’t pass in six tries?

Something is wrong if any student cannot pass a sheet within the six tries shown on the Rocket Chart. Do

not allow this condition to persist. Intervene with one of the ideas below.

l

If the student has never passed a timing, perhaps the child can’t really write that fast. Try testing the stu-

dent orally with the student telling you the answers. In oral testing the student says only the answers—

not the whole problem. If the student can orally answer at least 40 facts in one minute, then the student

is satisfactorily uent with those facts. The handwriting goals must be too high. Reset his/her goals at

the previous best and let the student move on to the next set.

l

The most frequent reason a student does not progress is because the student does not practice the

right way. In other words he/she avoids saying the problems out loud or skips the correction procedure

when they are hesitant. Or they will simply go on after a hesitation or error rather than going back three

problems and trying again to see if they are faster now. The remedy is for the teacher to practice with

these students as recommended and see if that makes a dierence. It often does. Let us tell you: This

is typically the “magic bullet.” It is fascinating really. Carrying out the practice procedure as we have

written it is VERY powerful. We wouldn’t lie to you. If the teacher practicing with these students does

help, arrange to see that they practice the right way consistently during peer practice. You may have to

change partners or watch over them daily until they start practicing the right way. Consider increasing

motivation through more rewards and recognition to keep students practicing the right way.

l

The student may not be trying because he/she is unmotivated. Watch to see if the student is doing

practice correctly or giving the test their best eort. Most often this is a result of failing to succeed

rather than a cause. (That’s really a very important understanding for you to have, so we’re going to

say it again!) Lack of student motivation is most often a result of failing to progress rather than a cause.

Consider practicing with the student. Think about ways to increase student motivation, including use of

student achievement awards and social recognition for success.

l

Watch to see that the student is “on-task” throughout the timing. Some students fail to realize that

looking up around the room during a timing will slow them down so much they won’t pass. (Really, we

kid you not. We’ve seen kids who stopped to check the clock several times during a one minute timing

be surprised that they didn’t pass!) If a student really cannot stay on task for 60 seconds, you might try

cutting the goal and the time in half—give a 30-second timing with a goal cut in half as well. That may

do the trick. It is often necessary to point out to younger students that erasing takes too long. Have you

ever watched a second grader erase something? One could grow old waiting. Point out to students that

perhaps putting a line through a mistake and writing the correct answer would save time.

l

If practicing with a student the right way doesn’t make a big dierence, then the student may be stuck

because he/she is “in over his/her head.” The student has ocially passed several sets without completely

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

20

mastering them. This should not happen if students always have to meet or beat their previous best—

but sometimes it happens anyway. A sign that this has happened is that they have several facts in the

set with which they are hesitant. You can tell just by watching over their shoulder as they complete a

timing—there will be hesitation on several of the facts.

l

The basic remedy for kids who are stuck is to back up in the alphabet until you nd a letter they can pass.

You can either test back all at once or have the student move back one letter a day until they do pass

after one day’s practice. Get them a new Rocket Chart to start over. Once you nd out where the student

is successful, make sure their goals are as fast as they can write—that you’re not letting them pass even

though they are hesitant on some facts. If you announce a policy of “six tries and then you have to move

back” and you announce this policy ahead of time, fewer students will get to six tries without passing!

Being proactive is the key here. It is important to cover all of your bases prior to bad things happening.

It is much better to pre-correct for something than to have to go back and re-teach a procedure or try to

introduce one when a student is upset and losing motivation.

How do I monitor students’ progress?

You monitor progress by the two-minute timings. You can nd the two-minute timings at the end of each

operation. Once a week or once every two weeks (we, of course, suggest every week.) have your students do a

two-minute timing of all the facts. (We made the tests so that a good many of the entire world of facts for the

given operation are represented. You do not have to gure this out. We wouldn’t wish that on you. It was a lot of

work to get it just right.) The purpose of these two minute timings is to see if they are improving in their knowl-

edge of the facts. (These timings don’t really teach, they just help you monitor progress.) On days when you do

a two minute timing, do NOT do the regular practice sheets. (Even we, the King and Queen of overkill wouldn’t

do that.)

Each time the students complete a two-minute timing, they will graph their results on their Individual Student

Graphs. They graph the number of problems they answered correctly in two minutes. But there are three dier-

ent Individual Student Graphs, you cry! Which one do I use, you ask? We have an answer, as you are beginning

to expect. Our suggestion is that students in grades one and two probably should use the Beginner graph that

only goes up to 45 problems in two minutes. We suggest grades 3 and 4 should use the Medium graph. We

suggest that students older than that should use the Advanced graph. But (and there’s always a but), that’s only

a rough guideline. If a student starts out on the rst two-minute timing with a score lower than the lowest num-

ber of problems correct showing on the suggested Individual Student Graph—use a lower one to record his/

her scores. Conversely, if a student appears to be ready to go out the top of the suggested level graph, get the

next level up and staple it into their folder. (And be sure to have a mini-celebration with that awesome student!)

As students progress through the program and learn more facts that they know instantaneously, they will

be able to answer more within two minutes. In the beginning they will only “know” a few of the facts and will

have to gure out as many as they can in two minutes. Eventually some students will instantaneously “know”

so many facts that they can answer about 40 per minute, or 80 in two minutes—but only if they can write that

quickly. There are enough spaces on the graph for each week in school. Have the students color in the bar with

the date closest to the date they took the test.

WARNING!

(Yep, another warning. We are being proactive too!) Do not reduce the criterion to pass each sheet,

as that will make it increasingly dicult for the students! They will not be learning each small set as

well as they need to and you’ll be adding more facts faster than they can handle. The cumulative task

will get more and more dicult. Only reduce the criterion if the student simply cannot write that fast—

otherwise, they can learn all the facts to the same speed as they learned the rst set.

© (2013) R & D Instructional Solutions.

Teacher Directions

21

How do I prepare for monitoring progress through the

two-minute timings?

You made the folders that we told you to make, right? You made enough copies of the Individual Student